From L’Atalante to L’Atalante:the story of a restoration by Pierre Philippe

December 1933

The winter was going to be are harsh one. The fountains of the Champs Elysees were frozen over. The canals were full of blocks of ice.

In this hostile environment, a certain Jean Vigo was making his first feature film, L’Atalante which began shooting on November 10th.

An inexperienced but stubborn producer, Jacques Louis Nounez, urged him on, even though the result of their first collaboration, a medium-length film entitled Zéro de conduite, had been banned that same year by the censor for its anarchistic spirit of revolt and its attack on public authorities, the priesthood and maybe also for its short glimpse of a child’s genitals…

Despite all that, Jacques Louis-Nounez persevered. He was the first to believe in Jean Vigo‘s genius. With the help of the same partners from Gaumont-Franco-Film-Aubert, he gathered the capital needed by the young director to attack a screenplay which Louis-Nounez had chosen for him for its supposedly tepid and apparently innocent populism: the story of the thwarted, but finally happy, love of a couple of young bargees, when the young wife gives in for a while to the temptations of the big city.

The project had two major advantages: the presence of Michel Simon who was already a well-known film star, thanks to Jean de la lune, La chienne and Boudu sauvé des eaux and that of Dita Parlo, already a star in Germany, who would find her first French-speaking role in L’Atalante.

The third protagonist was a young unknown actor, a friend of Vigo and the hero of Zéro de conduite, Jean Dasté.

The director’s friends were to be found in the remarkable supporting roles : Gilles Margaritis as the Parisian pedlar, Fanny Clar and Raphael Diligent, two old anarchistic journalists, as Juliette’s mother and the tramp Raspoutine, respectively. In addition, among the honest people running after the thief in the Gare d’Austerlitz, there were a few eminent members of the Groupe Octobre, Jacques and Pierre Prévert, Paul Grimault, Lou Tchimoukoff…

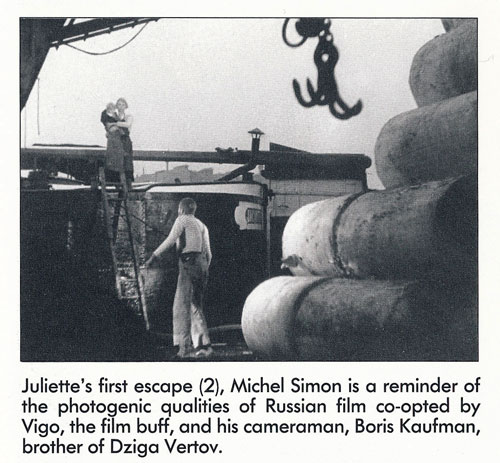

The technical crew was also made up of personal friends and Vigo’s tried and trusted collaborators: Boris Kaufman for the photography, Albert Riéra (Co-screenwriter) and Pierre Merle as assistants, Maurice Jaubert for the music and Charles Goldblatt as lyricist because L’Atalante, like all the other films of the day, had to have songs…

Despite the difficulties caused by the weather conditions and breaks in filming due to the poor health of Jean Vigo — who was suffering from septicaemia and would die eight months later — principal photography was completed at the end of January 1934.

The story of the curse on L’Atalante begins here…

Jean Vigo, exhausted by the filming, left Paris in February for the mountains, leaving Louis Chavance to complete the editing of the film. The latter had been chosen for his skill with sound editing and had been imposed on Vigo by the producers. But at least the director had been able to insist that his editor follow the shoot from day to day.

In April 1934, the editing was finished. Vigo, back in Paris, gave his approval except for a few details which he wanted to be able to change after the film had been screened to professionals. However, his failing health forced him back to bed. He would never get up again and would never see another image of L’Atalante.

The so-called « corporative » screening was held on April 25th. The exhibitors unanimously rejected the style of the film which they felt would only put off audiences who were supposedly looking for entertainment. This opinion was that of the distributors from Gaumont-Franco-Film-Aubert. They asked the producer Jacques Louis-Nounez to carry out major changes and cuts. He finally gave in: after the banning of Zéro de conduite, he couldn’t take another risk like this. Louis Chavance then brought the film down from 89 to 65 minutes. He cut into Maurice Jaubert‘s music and replaced it in part with extracts from Le Chaland qui passe, a popular song which was a hit at the time. This was taken even further: the film was retitled with this very title.

Le Chaland qui passe, a mutilated film by Jean Vigo, came out in September 1934 on the Champs-Elysées. Vigo’s friend, Pierre Merle, took photos of the decorated façade and hall of the Colisée cinema to show him. He now only had a month to live.

Flattering reviews couldn’t stop L’Atalante disappearing from the screen after three weeks. The film had, of course, been presented as romantic entertainment for all the family, but even though it had been shorn of its most disturbing images, the film resisted and the frivolous audiences wanted nothing to do with it. The film, the masterpiece, was put back on the shelves.

It didn’t reappear until October 1940.

The film had once more been changed by rushed hands. The references to Le chaland qui passe had been removed from the soundtrack and the title. It was screened at the Studio des Ursulines but — it seems — no more successfully than on its first release, despite a few attempts by the press of Occupied France to link its commercial failure to the troubles of a French film industry, in the hands of artistically incompetent decisionmakers of dubious racial origin…

It wasn’t until 1949 that Jean Vigo and this life’s work — three hours of film in all — became the hobby-horse of the French Federation of Film Clubs. This was more than a rehabilitation: it was an apotheosis, almost a deification.

Around this time, some people thought about putting L’Atalante back into its original form, as the 1940 film was clearly a shortened version of the original. From 1950 onwards, various restoration attempts were carried out, including one by Henri Langlois, president of the Cinémathèque Française, to whom Henri Beauvais one of the associate producers at Gaumont-Franco-Film Aubert at the time of the filming, but by then an independent distributor and owner of the material and rights, had given various unscreened dailies and cut sequences. There was also talk, without any real information, of versions restored by foreign amateurs. As a result of all these praiseworthy efforts, L’Atalante had an increasingly confused image among the swelling ranks of film-buffs. The few, relentlessly screened prints were wearing out. The original negative had mysteriously disappeared. One could say that, at the time, there were as many versions of L’Atalante in circulation as there were prints, without mentioning the few Le Chaland qui passe which were still about…

In 1985, Gaumont bought Franfilmdis, Henri Beauvais’s company, and — along with it — the stricken material of L’Atalante.

In 1989, the company decided that it was time to repair the injustice and errors of the past, committed, incidentally, under previous managment. However, it’s a stange quirk of fate that the restoration of L’Atalante should take place under a sign which has hardly altered since it oversaw the film’s attempted destruction…

Gaumont thus decided to start at the begining and travel back through the film’s tribulations. It began with a reexamination of the elements given to the Cinémathèque Française and which showed that they could bring about some amazing changes in the way L’Atalante was generally perceived.

The first operation was the cleaning up of the image and the sound, in conjunction with systematic searches for all material in circulation.

But the good new was still to come…

At the beginning of 1990, when the restoration had already started, an important discovery was made in the British Film Archive: a print from 1934, which had never left its cans. It was probably one of the first prints before the sacriligeous recutting of the film as it bears orginal cue dots and the title L’Atalante. With this print, we at last had a standard for the film, for even if this was not a version approved by Vigo, it was at least the closest we would ever get to it.

This discovery also incidentally disproved two legends concerning the poor quality of the sound and the deliberately grainy quality of the image: the original L’Atalante does not bear these scars of passing time and negligence. Another surprise came from Brussels and the Cinémathèque Royale which had an original of Le Chaland qui passe. We were thus able to discover that, despite general opinion, this version is far from perfect but has its qualities and, above all, contrains shots which were dropped for the 1940 recut! It is, paradoxically, often more complete than the exhausted old prints revered by the staunchest Vigoians !

We then had to be courageous and a little rash and, with all our love and respect for the work of Vigo, start to envisage the best way of fitting the shots into this reference print in order to make the perfect, even ideal copy, one that has never existed before, of a film that the whims of fate have condemned to atrophy and mutilation since its ceation.

We had to assimilate the many different versions of the screenplay and the hastily-scribbled notes in the margin, find our way through the changes caused by Vigo‘s genius for improvisation, consult the silent or sound images that have miraculously survived the winter of 1933 in their moving freshness, and try to decipher what happened within the creator’s fertile mind in order to be able to capture its elusive spirit.

But this was not enough.

We had to hunt down the last handful of people who had worked on the film and try to obtain from them the slightest bit of information that could shed light on the mystery of certain displaced shots and apparently incomplete sequences which were so beautiful that it would be criminal not to let them join their peers.

We met Claude Aveline, the executor of Vigo‘s will, his living memory. We questioned Henri Storck, Charles Goldblatt and Pierre Merle, the closest friends and collaborators and we found Jean-Paul Alphen, the last survivor of the three photographers. We rediscovered Jacqueline Morland, whom everybody had forgotten because her name doesn’t figure in the credits, even though she was the production secretary and worked on the continuity with Fred Matter. And, of course, we went to see Jean Dasté, in retirement at St. Etienne, to show him our precious discoveries…

Emotion and nostalgia mingle with the ever present memory of Vigo.

But can one reasonably expect these witnesses to be rigourously precise fifty-five years after an event, even if it was the filming of L’Atalante?

We had to take our responsibilities. Fully aware of the fact that we might well disturb some guardians of the temple.

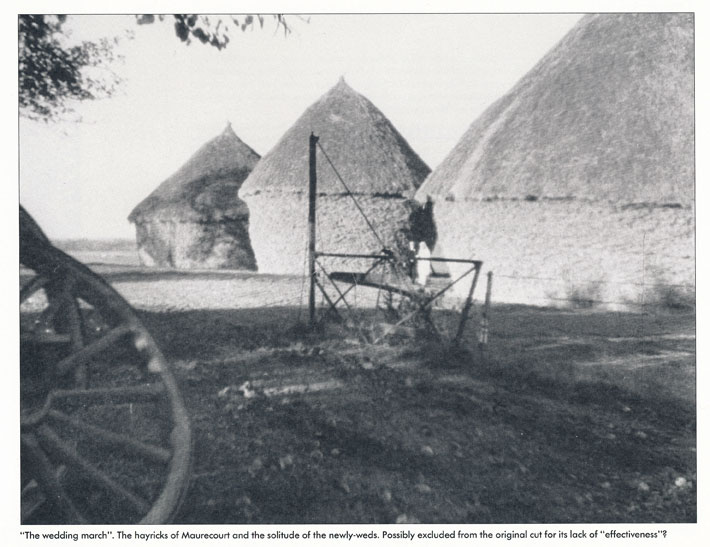

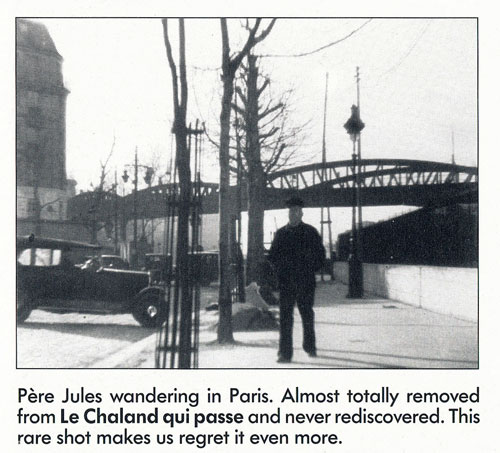

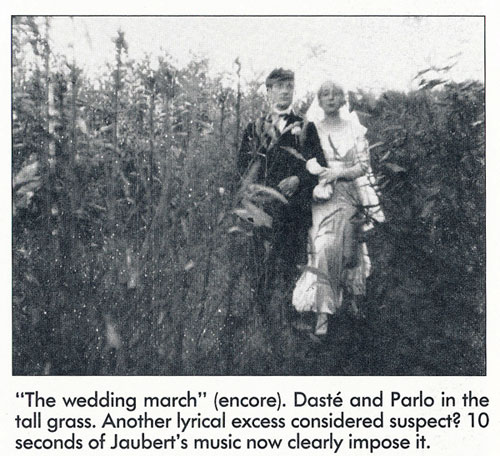

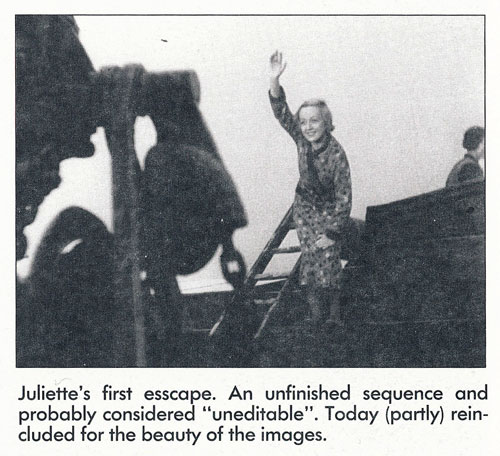

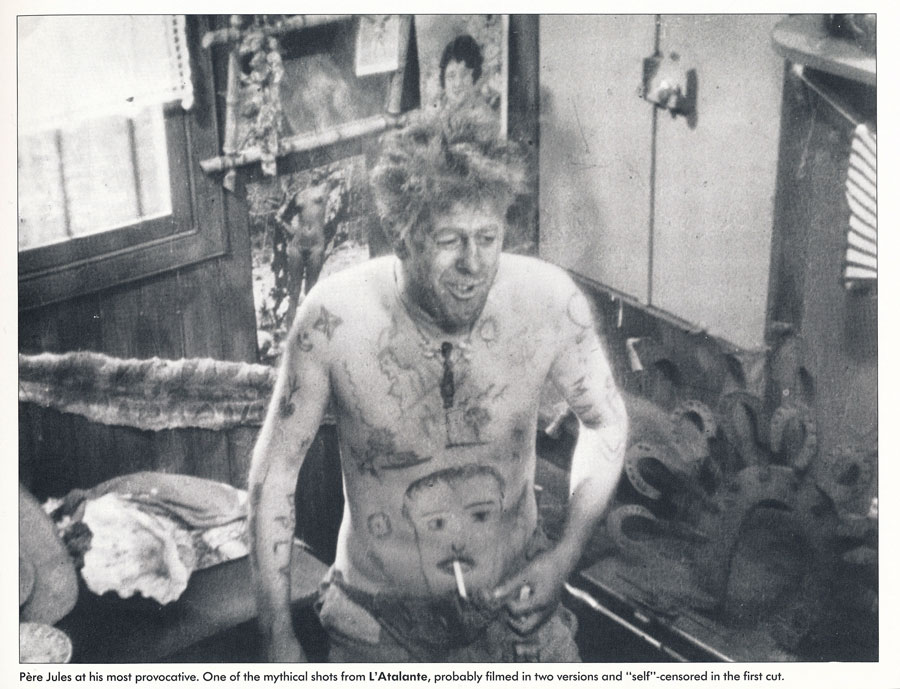

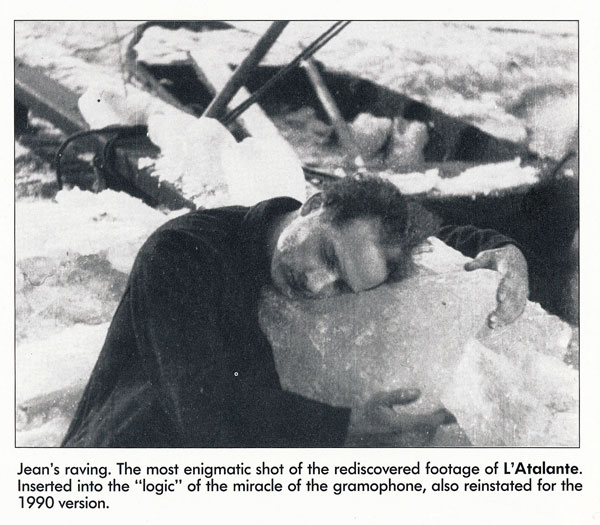

We’ll thus intervene in the very rhythm of certain parts of the film by reintroducing the sequence of Juliette’s first escape, which is missing from all the known versions; that of Jean wandering through Le Havre, before rushing towards the sea; and the sequence when Père Jules looks for Juliette along the Canal St. Martin. We’ll give a place to these moments which express a certain dilated time, as well as mobility, a sort of slowness which Vigo wished for. In so doing, we’ll allow a certain social setting to recover its rightful place and let the dockers do their work in the background of the drama. The wedding march will recover all its diversity thanks to the rediscovered footage as well as the musical intuition of Jaubert. We’ll have the newlyweds doing their washing and singing Le Chant des mariniers at the top of their voices. We’ll abolish one the great mysteries surrounding the film by — at last — showing Michel Simon with a cigarette in this tatooed navel. We’ll find the place for the flagrantly surrealist shot where Jean, carried away by passion and loneliness, hugs a block of ice. We’ll carry out Vigo‘s wish by having Père Jules fight himself. We’ll enrich and make more complex the sequence of the pedlar’s song which must have undoubtedly been greatly misunderstood at the time.

We shall do all this in the knowledge that Jean Vigo, given the conditions surrounding the filming of L’ATALANTE, could never have filmed one single shot that would not be used for the film or that would not fit in with his aims.

Our work will be signalled from the very beginning by a new title sequence which also contains new titles. We’ll dare to do away with those shoddy title cards which were full of spelling mistakes, false credit attributions and omissions.

Finally, we should like to thank all those people who, with their comprehensive collaboration, friendship and the faith they, like us, have in Jean Vigo‘s work, have helped bring about this rebirth of a film which, need we say it (but let’s say it anyway), is one of the pinnacles of film.

Pierre Philippe

The technical restoration

The image

Given the physical state of the Atalante print, we first had to repair the splices and, in places, strengthen the damaged perforations.

Then, the first step was a slow-speed solvant bath in an ultra-sound machine in order to remove, from the film, dust caused by mould on the emulsion.

Then a second bath in softened water with fungicides enabled us to halt the development of these fungi and thus improve the surface state of the gelatin.

The final step was the lubrification and polishing of both sides of the film. (Unfortunately, the indelible traces of the mould will remain slightly visible.)

The sound

For the first time in the history, we have, with the L’Atalante, restored the soundtrack of an old film with digital recording. This process consists of taking the sound elements of the best quality possible (often isolated parts of the nitrate film, optical negative, original prints, etc…) and copying them directly onto a digital master (OPUS LEXICON system, unique in France).

In this way, the sound can be analyzed and copied as many times as necessary without any loss of quality.

The rest is a trade secret… but requires a precise mix of resynchronization, with analog, digital and computerized treatments of the highest sophistication in order to remove all interference. (with the help of Bell X-1).

LOBSTER FILMS and RAMSES

The optical effects

For L’Atalante, optical effects are essentially used at three points in the film:

1 – the opening titles.

An animated image background filmed on a caption stand with a drawing taken from the shot of the film.

An attempt to diffuse the light throughout the image in order to create poetic atmosphere and expression.

The images thus obtained serve as a support for the titles and link up with the first real shots of the film.

For the titles: new graphics and new composition to follow the rhythm of the music.

2 – Michel Simon‘ pancratium (all-in wrestling) demonstration.

For this fight, which Jean Vigo – in this shooting script – had planned as an optical effect, but which wasn’t carried out as such in the final cut, we have researched the exisiting shots in order to fulfil Jean Vigo‘s wishes: Michel Simon seems to split into two characters and fight with himself to show Jean and Juliette « what all-in wrestling is ! »

The mixture of images is obtained by half-exposition and superimposition to obtain « 2 » Michel Simons fighting together.

3 – The final shot.

Filmed from a plane (the barge moving along the canal), the original shot is juddery and gives a clumsy, unpleasant impression. After a precise survey of all the frames of this shot, we have reset them one by one to eliminate as much as possible the unfortunate, uncontrolled camera movements.

The images have been doubled up to give more scope to this final shot.

Studio EXPOSURE

Leave a Reply